The intricate hand-drawn worlds of director Mamoru Oshii's films hide lessons for architects.

In most films, the scenery is merely a backdrop—the second fiddle to the dramatic tension between characters. But in others, the environment plays a leading role. For architecture buffs, few get better than Blade Runner's dystopian vision of L.A.

In 1995, Japanese director Mamoru Oshii released Ghost in the Shell, an anime film that portrayed a not-so-distant future that was wrestling with the onslaught of technology. Like Blade Runner, whose visuals inspired Oshii, the film depicts a mixture of slick newness alongside decaying remnants from the past. And while slivers of the scenery only appear on screen momentarily, they reflect a remarkable level of detail and craft in their production.

The Museum of Architectural Drawing, in Berlin, is currently hosting an exhibition called Anime Architecture, which delves into the renderings of urban architecture that appear in three films Oshii directed: Patlabor, Ghost in the Shell, and Innocence. All of the works on view are hand-drawn or hand-painted, and mostly originate from the '80s and '90s—a time when computer-generated animation was beginning to change how films were produced.

Why are these illustrations worthy of the museum treatment? Co.Design spoke with the exhibition's curator, Stefan Riekeles, about the architecture and urbanism of anime.

Co.Design: How did you become interested in analyzing anime through architecture?

Stefan Riekeles: I became interested in the whole animation culture by seeing the artists at work in their studios in Tokyo. I was helping another curator who was commissioned for a show at the Japan Society in New York to research anime culture around 2007 and 2008. I was lucky and was able to visit all of the artists' studios and have a look at their archives. Until that moment I didn't really care about Japanese animation. As soon as I saw their work, and the drawings, I was very interested.

These incredible illustrations are only visible for a few seconds on film, but you could look at them for hours. I was mainly interested in background art. Each scene has one background made from many, many layers of animated film. I was always more interested in the scenery than the characters.

What was the creative process behind these scenes?

With this exhibition we were focused on the films of Mamoru Oshii, who is very interested in the the transformation of megacities in Asia. When the bubble in Japan crashed at the end of the '80s, China took over [as a dominant economic force] and its rapid economic growth and the growth of the cities led to a lot of discord in the '90s. (Editor's note: A famous exhibition called Cities on the Move examined what was happening in terms of urban development and highlighted the changes Oshii was responding to.)

As an animator, Oshii reflected on the change of his environment through film. A high-rise would be built and after 10 years, it would be taken down and replaced by a bigger one. And in these three films of his we're focusing on, the theme is related to architecture. He used a special method to produce the "world," or the setting. It was rare to have a scouting team checking out locations, photographing them, and sketching a lot, like he did.

His environments are very realistic. It's not like a fantasy world. It's set in a real city, which is transformed and remodeled in the drawing. The artists started mostly with photographs and then the second step is the layout—or line drawings—and then comes color via the background painting. There's an additional process to figuring out the overall color and mood of the film.

For each cut in Ghost in the Shell, you can almost use exactly one photograph [the location scouts took] as a reference. The images are shot in black-and-white film so as not to interfere with the vision of the painter who colors in the backgrounds. The photograph is just to bring in the architecture and the structure. To give the whole art team an idea about the structure of the story, there could be thousands of photographs.

There are a lot of photos and drawings made for the film that are never visible [in the final movie], they're just there to create the setting. And the photographs are real locations like Tokyo or Hong Kong—Ghost in the Machine is set in Hong Kong—but then in some films you have locations which are fictional and cannot be photographed and for these the same amount of drawings are made. It's like a documentary, but made in drawings.

How do the artists meld their present-day surroundings with these visions of the future?

Ghost in the Shell was kind of an homage to Blade Runner. Some shots are almost copies of Blade Runner scenes. In Blade Runner, L.A. was infused with an Asian flavor to make it exotic, strange, and set it off from the present. Gadgets show the city's mechanical transformation. But to transform it from a cultural standpoint, and the Japanese animators used exactly the same method—taking references from mainland Asia—to make the city a bit strange and to set it apart from the everyday.

Oshii wanted a city that is futuristic, but not too much so. Since it was 10 or 20 years in the future, so it needed to be similar to what we have today but a little different. And for that difference, that oddity, and creating that depth, he used Chinese characters in the signs or advertisements so that Japanese audiences would feel a bit estranged. They could almost read the characters, but not quite. That's always the trick.

The other aspect is that the story has to be believable. To that end, the setting needs a degree of believability. It has to be advanced, but still close enough so it can sustain a story. So a fictional city needs to look as if it could work. It needs to feel as if it was constructed. That's where the concept designers and mechanical designers come in. They think in an architectural way and are constructing cities from scratch as if they would actually work. To make that impression, you need to really be detailed. You have to know how the doors close in these buildings, how the elevator works. If it's powered by a nuclear engine, then you have to design the engine. It's like a construction office working in the background to build that city.

The films you chose to highlight were produced when the shift from hand to computer animation was taking place. What were the biggest artistic differences that resulted?

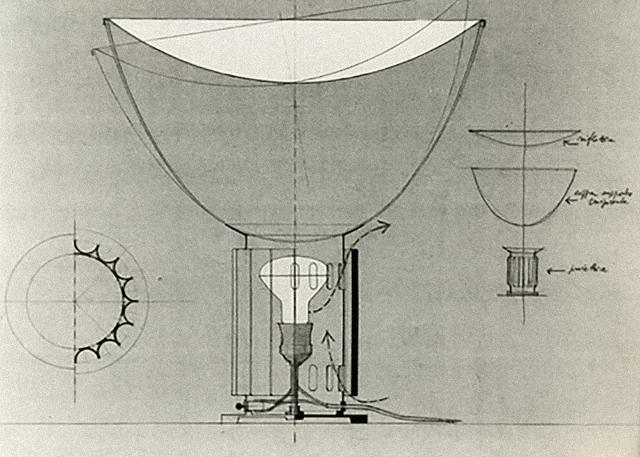

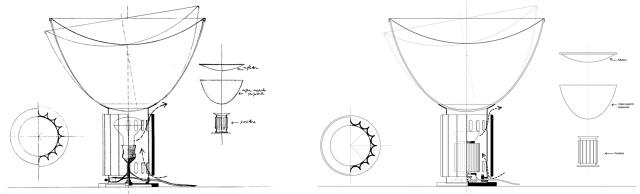

The real "architect of the future" is Watabe Takashi; he was the concept designer and layout artist [for Oshii's films]. He's not an actual architect, but he works in a way as if he was an architect. So you cannot build his buildings in reality. They look structurally correct, as if they would be possible, but for film it's just the image that counts.

He was born in '54 and studied math but became an animator in his twenties and draws everything by hand. Because he has a geometric thinking, he can draw all of these perspectives very fluently by hand but he sometimes uses computers. If he had a high-rise building he would design the walls and silhouette in a computer because that makes it easy to figure out camera perspectives and distortion angles. But every detail he needs—like pipes and lights—he would do by hand because it's much faster to print out the wire frame of the building and draw in the details. If you have to model everything in the building on a computer, that takes a long time. It's much faster drawing details by hand and rendering the main structure in the environment in 3D.

When he showed me these drawings, I thought, "Wow you have almost the whole movie in 3D renderings but there are still drawings and paintings on paper." From my perspective, I thought if you have everything in 3D why not just render it? Why would you go in by hand? He said it takes too much time to draw a pipe on a computer. These guys are thinking about time efficiency. The only thing you have to pay for in animation are man hours. The only thing you need is time. So the faster you can be, the better. Everybody has their own strategy to achieve the best results as quickly as possible. So that's the computer aspect. Sometimes backgrounds are all drawn by hand because the artists can't stand the look of computer animation. They need the handmade feeling.

The key animators and art directors and people higher up in the hierarchy, they are older now and they were all trained on on a drawing table and lightbox. Japanese animation has a look where movement is interrupted; it flickers a bit. That's achieved by something called "limited animation." The characters don't move smoothly, even if they are rendered in 3D. That gives the viewer an additional effect of immersion. The senior people sit behind the 3D guys and tell them which frames to delete [to achieve the flickering effect]. They're working like sculptors, taking away [material] and working in negative space.

It's interesting that Ghost in the Shell talks about the change of society thought computer technology, but the whole film is handmade.

What can designers and architects can learn from examining these paintings and taking a look at the environments the animators created?

The drawings have an enormous depth and quality, which you cannot appreciate [fully] when you watch the film the background just appears for a few seconds. It's worth looking at these things for a much longer time since they are intricate and well done. The designers I talked to so far were all fascinated by the quality and craftsmanship of these drawings because they're incredibly detailed.

An interesting aspect is that [the background animation] is all serial work. If architects build a building or a house, they tend to focus on a singular building for a long time. For the film's animators, it's more about building a whole world and the whole world needs to be consistent in its look and feel. Architects tend to look at their buildings from the outside in; switching perspectives to looking from inside the building to what surrounds—like animators have to look at the entire world—it is very interesting. A building can be understood as a narration of spatial events. There is an interesting relationship between constructing a film set and constructing a new building—you have to imagine and maybe draw and sketch angles that you never really see [in the final product].

Anime Architecture is on view at The Tchoban Foundation Museum for Architectural Drawing until October 16, 2016.

[Ghost in the Shell (1995): © 1995 Shirow Masamune / KODANSHA · BANDAI VISUAL · MANGA ENTERTAINMENT Ltd., Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004): © 2004 Shirow Masamune / KODANSHA · IG, ITNDDTD]