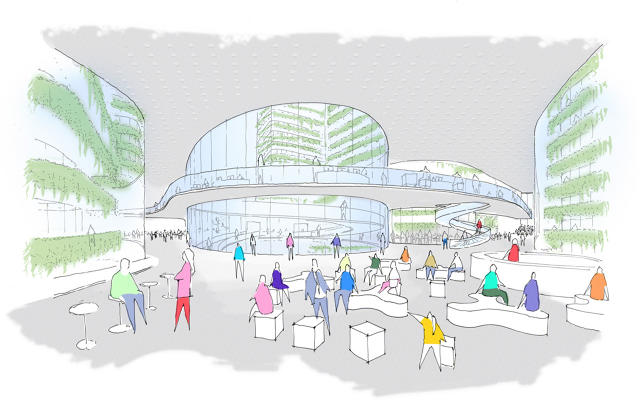

Picture a gleaming building wrapped around an expansive tree-filled courtyard. All the walls are glass so you can see what's happening in the ground-level retail and open-plan offices on the upper floors. In lieu of cramped hallways there are wide-open walkways and a snaking ramp that ascends to a rooftop lawn. Apartments are close by and there's a constant hum of activity and interaction throughout. This is the image of a forthcoming innovation district in Miami, Florida.

In business, everyone is racing to develop the next big thing. Similarly, cities and developers are capitalizing on this by building entire neighborhoods to foster innovation. But one question lies at the heart of the trend: Can innovation really be designed?

Innovation Districts, Defined

Planners have cycled through various city building models over the decades. New Urbanism, Smart Growth, and Transit Oriented Development, for example, have fallen in and out of favor. Though they've formally existed for over a decade, innovation districts have generated substantial momentum recently.

22@ in Barcelona, which broke ground in 2000, was one of the first commercially developed, city-designated innovation districts. Joan Clos, the city's former mayor, lead the initiative to transform a derelict 494-acre industrial zone into a tech hub. Strategically located near Barcelona Activa, a business incubator, the goal was to provide space for companies to "graduate" into. The master plan was successful. Since 2000, 4,500 companies new companies entered the district, 47% of which are startups and 27% are considered knowledge-intensive businesses. Scytl, an electronic voting company, emerged from the neighborhood and is one of the most successful startups from the district. The workforce in the neighborhood has grown 62% and it's home to thousands of residential units, walkable streets, and educational institutions. 22@'s success proved the innovation district model can yield successful city building.

Moving stateside, Seaport Square, in Boston, was one of the first ground-up innovation districts, which was designated in 2010 by mayor Thomas Menino. In 2014 efforts to build new ones hit a fever pitch with cities from coast to coast approving master plans. Innovation districts are underway in Brooklyn, Chicago, Portland, San Francisco, Fremont, and Seattle. There are established innovation districts in cities that surround Tier 1 research universities, like Cambridge, Massachusetts (MIT and Harvard); Atlanta (Georgia Tech); and Pittsburgh (Carnegie-Mellon).

An innovation district can be planned from the ground up or areas within cities can evolve into one. At its broadest, an innovation district is composed of cutting-edge research (usually from of a major academic institution), business incubators, startups, advanced technical networking, commercial spaces, housing, transit accessibility, social spaces, and amenities. It goes beyond generic "mixed use" construction to embody a recipe of specific attributes that, in theory, fuel innovation. Moreover, everything is packed into a dense area.

The idea is that when you mix all these things together, people, who in the old model of city building might remain siloed, have the opportunity to mingle. And being the social creatures that they are, then spark conversations with those outside of their direct discipline and potentially come up with incredible new ideas. In theory, innovation districts are the antithesis of the isolated business parks and corporate campuses that define Silicon Valley.

What Does An Innovation District Look Like?

While the composition of an innovation district is more or less set, its physical presence is more ambiguous. The common themes, however, are transparency, flexible spaces, and opportunities for people to spontaneously meet. This is where the hand of the architect enters the fold.

Bruce Katz, is the vice president and director of the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institute and co-author of a paper titled "The Rise of Innovation Districts." He's spent the last few years traveling the country and researching this burgeoning urban model. While Katz primarily analyzes facts and figures—the quantifiable economic indicators of innovation—he also keeps an eye on design. "My own view is that design and architecture matter quite a bit, but it doesn't necessarily in reality," he says.

To Katz, the most successful districts promote the "bump and mingle" effect. Inside, the spaces are flexible and accommodate coworking and collaboration. Outside, the public spaces are animated and vibrant, whether its from pop-ups or public programs or just a welcoming space. "I wouldn't call it all 'high design' but giving a sense that it's a destination and a cool place to work is tactical urbanism to the best degree."

In Boston, Hacin + Associates was commissioned to build District Hall, the flagship structure in the 23-acre Seaport Square innovation district located on the city's waterfront. Along with the New York–based firm Kohn Pedersen Fox, Hacin + Associates also developed the site's master plan.

"Innovation districts don't have precedents for building form," Scott Thomson, a senior associate at Hacin + Associates and District Hall's project manager, says. At 12,000 square feet, District Hall houses a restaurant and cafe, flexible meeting and assembly areas, and workspaces. It also hosts seminars and events.

"Design was an important part of the building since it would be a symbol of the district," Thomson says. "It needed to get the point across of ideas coming together to start something new. What was once a vibrant district about the import and export of goods is now about the import and export of ideas."

The building is as much about metaphors as becoming a beacon for the burgeoning district. Large expanses of glass offer transparency into the structure and invite a dialog with the city. The finishes—like corrugated metal cladding and concrete floors—and silhouette nod to the site's industrial past. Idea Paint coats the walls inside to welcome impromptu note taking and punchy hues—like chartreuse, the unofficial color of disruption—enliven the rooms. Moveable furniture encourages people to carve out their own spaces.

While the sleek design sounds like a tech startup hallmark, it serves a measured purpose: luring a certain type of person to the district and forging a space they want to inhabit. "The clientele the city is trying to attract lends itself to having a certain design ethos in the district and the buildings themselves," Thomson says. "A lot of what happens here is fundamentally creative."

Katz notes that there is a larger cultural shift toward open innovation in play. Companies aren't conducting research and development internally, he says, they're looking for ideas wherever they can get them.

Today's wellspring of new research often comes thanks to universities, which benefit from federal grants and have access to equipment and resources that the average business doesn't. Intermediaries, like startups and entrepreneurs, unlock these ideas and bring them to market. "If you want to build an economy, get an advanced research university to move in and wait 50 years," Katz says. Kendall Square, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is a successful innovation district to Katz; University City in Philadelphia, which is anchored by Drexel University and the University of Pennsylvania, is another one.

Katz points out that universities—anchors for innovation districts—are starting to de-centralize, for example Cornell's new tech campus on Roosevelt Island and UCSF's Mission Bay outpost. "This is where architecture and design can help," he says. "As these institutions move around, how can they be designed to welcome open innovation?"

If You Build It, Will They Come?

This summer, the New York-based architecture firm SHoP, Dutch landscape architecture firm West 8, and developer Michael Simkins revealed renderings for the aforementioned innovation district in the Park West neighborhood of Miami, Florida.

"We're trying hard to make sure it's not a buzzword, that it's a real thing," Vishaan Charkrabarti, a principal at SHoP, says.

This isn't the first time SHoP has worked on an innovation-oriented project. Its Botswana Innovation Hub, in Gaborone, is currently under construction. The 300,000-square-foot project houses an HIV research lab run by the Ministry of Health in partnership with Baylor, Harvard, and the University of Pennsylvania alongside commercial spaces.

"The country has a small population and is well educated," William Sharples, also a principal at SHoP, says. "Its main exports are beef and diamonds and the Hub is helping to take the country into the next millennium. Working with the International Finance Committee within the World Bank, we identified the critical ingredients to have something where innovation and creativity can happen: research, biotech, information and communication technology, an academic relationship, and business opportunities. It's a microcosm of what everyone's talking about when they talk about innovation districts and a lot of those ingredients play into Miami."

The Park West development is about 10 acres large—the size of four city blocks. The designers conceived of the master plan as an urban campus with shared public plazas, 3,850,000 square feet of office space, 2,400,000 square feet of residential space, and 250,000 square feet of retail. Walkways and shared corridors link everything together. SHoP projects that the development will bring 13,000 high-paying jobs to Miami.

"We focus on the physical conditions needed to facilitate 'serendipitous encounters,'" Charkrabarti says. "It's about building in a dense, highly walkable environment—an urban incubator."

SHoP calls the innovation district radical mixed use and supports creating buildings that can adapt over time to suit the needs of whomever uses them. It's flexibility and longevity by design. The firm acknowledges that de novo cities rarely look right on day one, and they require time to get their footing and become populated.

"It's not about putting people under a Bucky Fuller dome," Chakrabarti says. "It's about reinventing cities and infrastructure so people aren't in these 20th-century bubbles, segregated physically, socially, and technically."

"Millennials don't want to be prescribed," Sharples adds. "You have to give them a platform where they can progress—it's about getting the right ingredients in place and having the right building systems and infrastructure to support them."

What SHoP calls the Miami Innovation Tower is the development's marquee structure. The controversial 633-foot-tall torqued form is capable of displaying images, thanks to digital billboards integrated into its skin, and announces the district's purpose as a technology-oriented neighborhood. And while a veritable 63-story screen speaks the district's character, so do the project's tree-lined streets and sidewalks.

"In a technological era, we need to walk more and be in contemplative environments," Charkrabarti says. "You get so distracted by tech that in order to innovate you need to step back and take a breather. You need nature."

To that end, the Miami District has ample green space on multiple levels, including on the roof. What's also remarkable about the conceptual drawings is the presence of pedestrians throughout. The master plan is built around the human scale and speed, not cars, and to SHoP their vision for an innovation district is emblematic of a new direction in city building.

To Sharples, the design of the district is symbolic of what people desire from their cities: a place where it's easy to live their lives and that's accessible on a number of levels. Housing, a challenge in large cities, is a significant part of the innovation district as it includes micro-units targeted to the workforce its expected to support. "Not everything should be about a government program to have affordable housing" Sharples says. "There's also a responsibility about infrastructure to make affordable neighborhoods accessible. If people can live near where they work, there's a huge time savings. In a service economy, time is the most valuable resource."

Towards a New Architecture

While the 20th-century city was constructed around cars, the city of the future will be tailored to people.

"If you look at the future of the city where we're driving less, you can start scaling city blocks not around the turning radius of an 18-wheeler but to the turning radius of a three-wheel electric vehicle," Chakrabarti says. "You start generating street grids we haven't seen before the advent of the automobile. It's a completely different paradigm from the twentieth century where you thought about the highway, the campus 10 miles from downtown and 20 miles from your home."

While investment in urban form and making a place seem beautiful and attractive seems subjective, it's becoming a potent driver for growth. As consumers, we're becoming savvier about what's around us and more knowledgeable about design. While we surround ourselves with products that fulfill a particular aesthetic or expectation or experience, what we demand from cities will is also becoming more sophisticated. To put it bluntly: all those Apple fanboys and girls will want a city to match.

In the context of building a successful innovation district or a design district, populating it with a certain type of person is the critical element. Design can undoubtedly foster those connections, but it goes beyond looks. Above all, a district needs to work and fulfill the needs of its denizens—it's about experimenting with visionary models for cities and how design can facilitate it.

"In the 20th century, education, technology, and culture were thought of as 'etcetera'—great Christmas ornaments," Chakrabarti says. "We have to think about it in reverse, that they drive urban growth."

A similar philosophy of walkability and proximity governs another large-scale local neighborhood development, the Miami Design District spearheaded by developer Craig Robins. Geared toward arts and culture, the conclusion that design matters is more clear cut. While the form of the innovation and design districts have their own flavors, the composition is nearly identical: walkable streets, open space, residences, buildings constructed to the human scale, commercial storefronts, business, and a major institution (in the Design District's case, the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami). And like the Miami Innovation District, it has a roster of big name architects steering the overall design, like Studio Gang, Sou Fujimoto, and Aranda Lasch, to name a few.

"To have a fertile creative environment, we have to have interesting architecture," Robins says. "Ultimately, it's a question of the quality of life and when there's a greater sensitivity to design and art and the creative process, I think things are better. When we talk about neighborhoods, they can be for anything. A neighborhood that will be successful will have an intelligent urban design first."

Both Robins's district and SHoP's are built around similar progressive urban design tenets—but it's who moves in that will ultimately deem them successes.

All in a name?

On paper, an innovation district sounds like a win-win for cities and developers. Invest in a site and reap the the profit from building a multi-million-dollar structure or increase the job force and fortify economic health. However, the aspiration toward innovation isn't a guarantee for results.

Katz cautions against calling a neighborhood an innovation district when it doesn't have the bona fides. "This is an idea virus," he says of the rapid proliferation of developers claiming they've built innovation districts. He says the true purpose of an innovation district is idea generation and the commercialization of research. When he analyzes an innovation district, he bases it on economic factors, not on surface characteristics. "This is a market dynamic, not a government program or a real estate gimmick," he says. "Labeling something as innovative doesn't necessarily make it so."

The media has nicknamed a few of the innovation hubs around the globe that are trying to replicate Silicon Valley's unbridled success. There's Silicon Beach, in Los Angeles; Silicon Alley, in Manhattan; Silicon Lagoon, in Nigeria; Silicon Savannah, in Kenya; and Silicon Plateau, in India. The aspiration is certainly there, but the results might not be.

Katz is at-work on an auditing tool to separate the actual innovation districts from the aspirational ones. It's centered around five categories: a critical mass of activity, connectivity, a competitive advantage, diversity, and physical qualities (architecture, amenities, location, for example). "Our view is that the quality of the place matters to the innovative process today," he says, but it's hard to quantify and it's only one element in the ecosystem.

While aspirations certainly abound in de novo innovation districts, it takes more than good intentions and available real estate to make it a reality. Take Tony Hsieh's Downtown Project in Las Vegas. The Zappos founder pumped $350 million dollars into redeveloping a neighborhood and brought in 65 startups and small businesses. It's hit a rough patch since that initial cash infusion. According to an NPR report, the Downtown Project hasn't been profitable, it laid off 30 employees recently, and Hsieh is giving it two more years to see if it breaks even.

The lesson learned here is that you can construct a neighborhood to have the physical characteristics of good urban design, but it takes more than that—it needs time and it needs the right mix of people as a catalyst. Even then, there's no guarantee that the next Google or Facebook will emerge from the district.

"Developers are trying to get a price premium, which is something I totally understand," Katz says. "'Smart growth' was a '90s phrase that was about promoting reinvention but then it was co-opted by the real estate community. 'Innovation district' has the potential to be abused."